HDB Affordability Crisis: A Case for Strategic Flat Reserves

Front loading my disclaimers, so you can exercise your scoops of salt as needed.

Disclaimer

- I am a Singaporean.

- I purchased a resale flat, and I write against my own class interests here.

- I have received family support for my purchase and acknowledge such privilege exists, but not for all. A workgroup should be formed to investigate the effect of family wealth on HDB purchases, but that is outside the scope of this discussion.

ISSUE: The Staircase Effect of HDB Prices

Part A: Market Forces

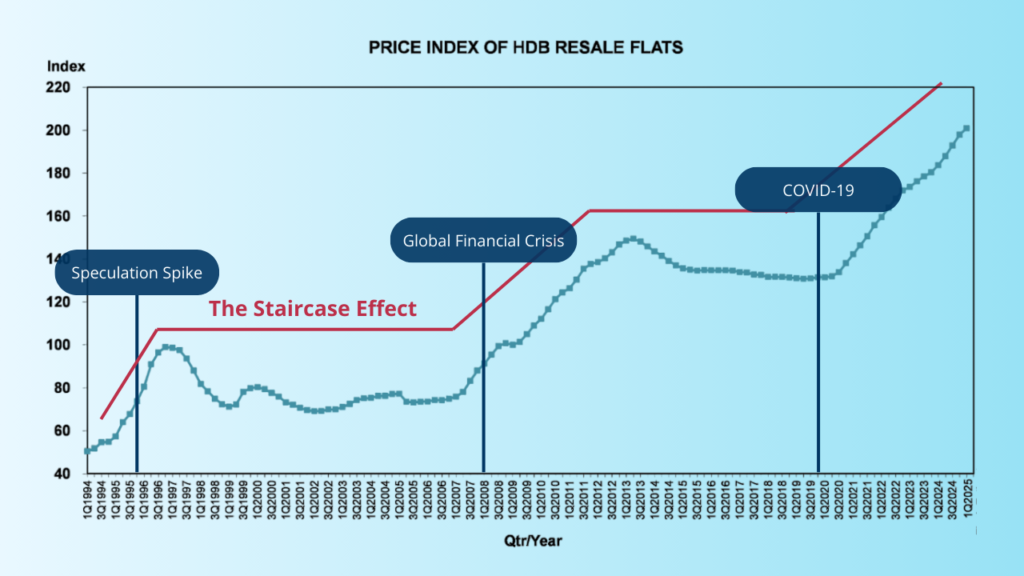

I’m sure this graph is familiar to you by now. Observe how HDB prices would spike, only to return to a plateau, with each plateau higher than the next.

(source: HDB)

Demand Increases

Let us consider the reason for each spike. The 1995 spike was due to increased speculative demand for housing property, driven by the overall Asian purchasing frenzy of the time, while the 2008 spike was due to increased demand for HDBs from private property downgraders that were driven due to the global financial crisis—many of whom were coming off some years of accumulated property appreciation on a higher asset base, and would be comparatively wealthier versus the first-time buyer.

Then, more recently in 2020, the economic crisis, paired with subsequently high interest rates that elevated mortgage pressures, drove private owners to downgrade. While a 15-month exclusion period may have slowed this demand, it likely only evened the demand out over a longer climb rather than decreasing the overall amount of demand.

Supply Decreases

The 2020 spike was also a perfect storm of supply issues, which the CNA documentary covers in good detail, with labour shortages and slowdowns arising directly from COVID-19, and the supply of precast concrete from Malaysia being disrupted by border closures.

Demand Inelasticity

Adding to that is the fact that housing is a necessity. Even if otherwise, it is a critical life journey purchase for any married couple or single Singaporean with parental conflicts.

This makes housing demand inelastic, meaning any shortage in supply leads to a large spike in price. But given our higher propensity to stay with our parents into adulthood, why don’t Singaporeans put off the housing purchase until the market declines?

The issue is because it is expected (and rightly so) that the housing price will never decline significantly, and if one doesn’t buy a house now, they will only lose more as housing continues to appreciate.

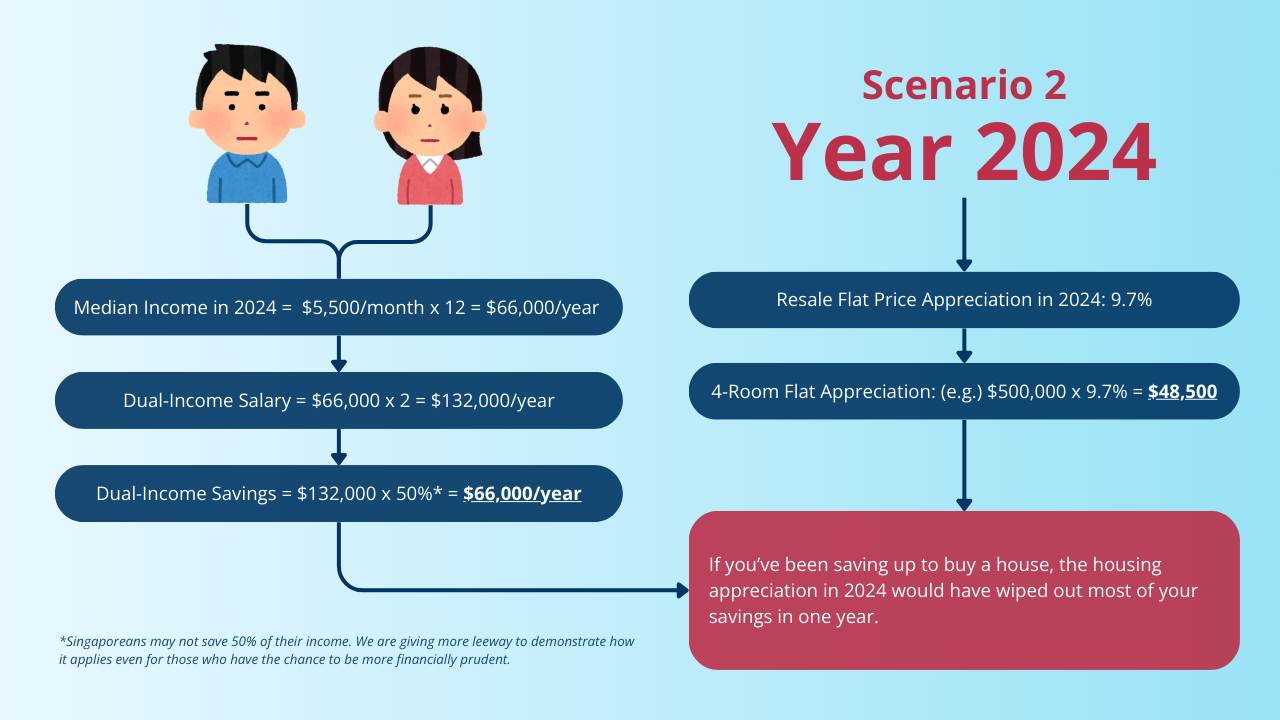

And each point of appreciation is massive, as it is a percentage of a hefty sum (the most hefty sum many Singaporeans ever see in their lifetimes). The 12.5% appreciation we saw in 2021, on a base of a 500k 4-room flat, equates to 62.5k, easily the entire annual savings of a dual-income graduate family.

A whole year’s worth of hard work and progress wiped out because of a put-off purchase is plenty hard to swallow, so no wonder there is a necessity to buy now.

Later, we will go into why Singaporeans have a legitimate expectation that prices won’t decline. For now, this expectation and how it shapes the decisions of any reasonable Singaporean household, demonstrate that no matter how many alternative shelter arrangements there are (rental, parents, etc.), it still does not dent the demand inelasticity during a spike incident.

People buy not because they need a roof over their head now, but because they need to buy it eventually. If they don’t buy a house now, their precious savings are at risk. Thus, if there are any supply shocks, we can expect prices to hike up.

Supply Inelasticity

Lawrence Wong has said before that “I wish I can wave a magic wand and produce instant flats”. However, there are real limits to construction (that he can fortunately externalise the blame to).

The fact remains that under the current provision model for new HDBs, we cannot build as fast as demand comes in. Even with a 15-month exclusion, this pales in comparison with the time taken to take a BTO project from conception to key issuance (3.5 years at minimum, much longer in actuality).

Even if the price of resale flats or BTOs increases dramatically, the main supplier of affordable housing (HDB) cannot simply increase supply in response to demand, an effect that worsens in the presence of supply shocks like COVID-19.

This time gap between demand shocks and supply ramps represents the high supply inelasticity, which means any increase in demand creates a sharp increase in price.

The Ones Who Lose Out

When the price increases with demand, the spare capacity must come from somewhere eventually. And if no new BTOs are built in a timely response to the demand, where does the capacity come from?

Part of it will come from condo upgraders or from families that wish to sell and stay elsewhere, for the price finally rises high enough for them to consider doing so.

However, much of the supply will come from families that are too wealth-poor or income-poor to afford buying into the market at resale. Thus, they forgo their purchase for those who can bid higher. These families must eventually still pay the higher cost with their savings wiped out when buying later, while the wealthier buy now and manage to retain their savings by foregoing the future property appreciation costs. The preservation of a wealthy person’s savings appears to be funded by a wealth transfer from the less wealthy, who experience a future wipeout of their savings.

At the same time, families that actually need flats more urgently have lower odds of getting flats from BTO lotteries, as families that could have afforded to wait or families that have been priced out of the resale market move to add their numbers to the ballot.

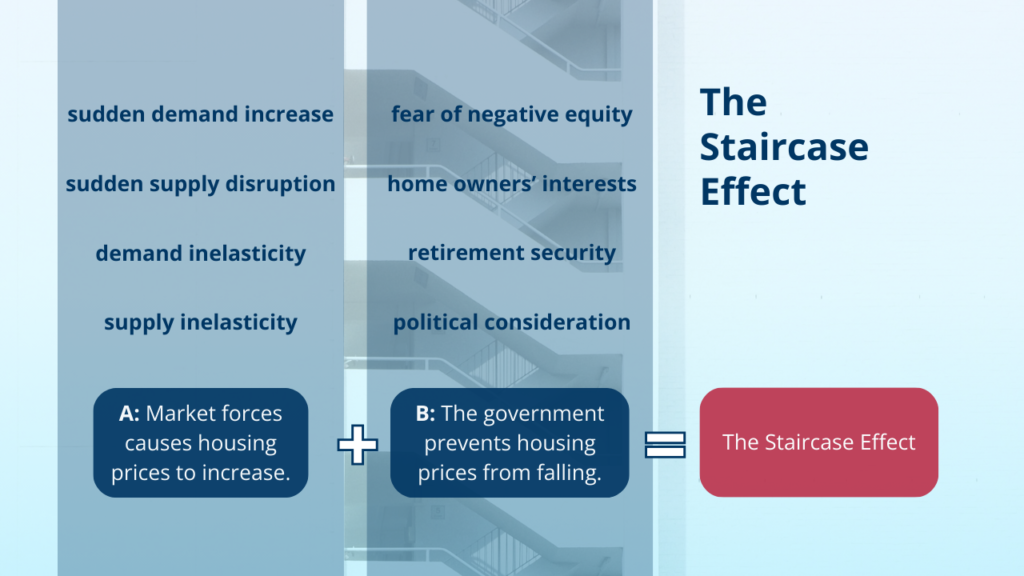

Conclusion A: Price Increases are Caused by Market Factors

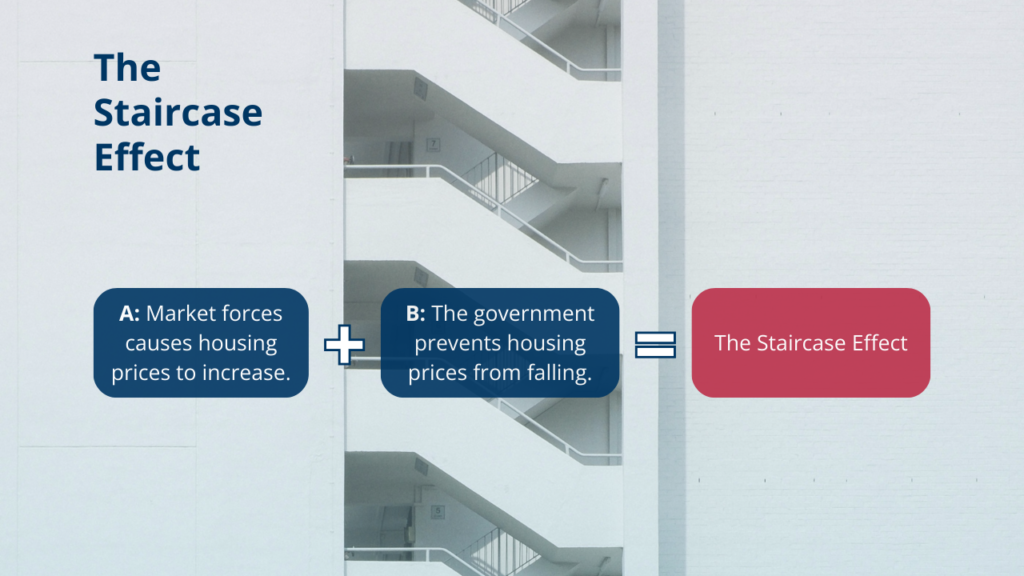

So these market forces, many outside of the government’s control, explain the upward spikes of the HDB prices. This outcome makes sense for any commodity that is exposed to the free market. But what explains the plateau?

PART B: The Political Pressure Against Negative Equity

In a free market, the increase in price will eventually trigger an increase in supply, which will eventually bring the property back to its pre-spike price. However, that is not what we see here.

The central issue is that of negative equity. Negative equity arises if a homeowner purchases an HDB at a high price during a period of rapid appreciation, only for the price to fall afterwards due to market forces.

This means their mortgage exceeds the resale value of their flat. This is a crisis in many ways.

The Financial Insolvency Issue

This is the more extreme issue. If negative equity is so great that it wipes out the down payment of the flat and then some, the financially prudent decision by the individual is to default on their mortgage and purchase a resale flat directly from the depreciating market.

This was the famous issue for America’s Subprime Mortgage Crisis, where spiralling default caused the banks to hold empty houses they had to let go of at a loss, which then further lowered prices, which then further drove defaults, and so on—until the financial system went into crisis.

This is not as large of a concern in Singapore, where defaulted flats would go to the HDB. Unlike American banks that were eager to sell their housing stock before other banks sold theirs first and tanked the market further, HDB has a unique position as the primary receiver of defaulted flats (for HDB mortgages) and the sole provider of new HDB flats. That means that they can hold onto vacant, defaulted HDBs without any fear of long-term loss of value, as they can simply limit the future output of HDB flats and drive the price up to sell without loss in the future. To the degree that HDB is willing and able to do that, local banks that receive flats via default will also be unlikely to sell at a loss—both effects preventing a default spiral.

Thus, while this fear looms large, it is only secondary to the other effect of negative equity—the personal retirement asset issue.

The Personal Retirement Asset Issue

(source: SPH Razor)

The HDB has long been promoted as an appreciating asset that Singaporeans can put their retirement savings into to secure a good retirement.

In a sense, the “can” is a soft “must”. Compared to the faraway interest returns earned by sitting in the CPF, a housing purchase/upgrade allows one to immediately enjoy the benefits, all while putting the money into an investment asset which is no less lucrative and very much secure.

The size of the investment is no joke. For many, it comprises between 10% to 30% of their monthly income for the next 10 to 25 years. For many, this is the largest sum they’ve comprehended, and likely the largest they will ever comprehend.

Now imagine if that sum takes a big cut, or if you go into negative equity of 10% of that sum.

Hopefully, it’s not the end of the world, but it would stir some unhappiness in the citizenry. Unhappiness that might display at the ballot.

At a 90.8% home ownership rate and an ever-ageing population, it may be argued that the political interest to preserve flat values is higher than the political interest to make flats affordable to new home buyers. The very fact that we are willing to put affordability against homeowner interests is itself a testament to the maturity of our democracy, but that still does not stop the government from feeling the pressure to keep homeowners’ retirements safe.

An actual widespread decline of HDB prices has never been experienced before, and it’s uncertain how the population will react. Perhaps, the soon-to-be retirees will be gracious, willing to live their retirement years more modestly with the knowledge that the next generation has benefitted from their sacrifice. Or perhaps they will be bitter or impoverished enough that, out of anger at a government that swindled their life savings into a depreciating asset, they vote that government out.

We do not know for sure, but understandably, the government doesn’t dare to test and find out. So, what happens?

Shrinking BTO Supply and Maintaining Sales Prices

To prevent homeowners who have bought into HDB flats at an inflated spike price from going into negative equity, and to protect the gains made by other HDB owners, the HDB makes use of their status as the monopoly supplier of affordable housing and simply ramps down the supply.

When it does sell, it can also choose to set a higher price and wait until it sells out. There are 3 reasons it can do so:

- HDB is a monopoly supplier of affordable housing, and cannot be undercut by a competitor.

- Development expenses are taken out of the “other pocket” of CPF, and the land price component could theoretically be owed to the “next pocket” of the government reserves. Neither of which would hound HDB to liquidate its stock.

- A self-fulfilling prophecy, because the HDB is a monopoly supplier, they can and will slow down production as well as set an elevated price at the BTO level, it is unlikely that the resale price will fall below the BTO price, making BTOs always profitable no matter the entry price. This effect ensures that the demand for BTOs, even at elevated prices, will eventually come.

Are BTO Prices Affected By Resale Prices?

This is a good time to address the myth that BTO prices are unaffected by resale prices, and that the rising resale prices do not affect Singaporeans because they can always go for BTO. The CNA documentary directly captures the workings of HDB’s BTO valuation department, who use nearby resale values to inform their valuation decisions.

source: CNA

So, rising resale values will result in rising BTO prices. Speculative buyers, represented by 13.4% of HDBs sold within the year of MOP, may note that BTOs are still profitable. But the other majority, 86.6% of HDB buyers who are staying in their flats for the long term, have to live with the higher mortgage base.

Returning from the tangent, HDB’s production slowdowns ultimately prevent further price drops, leading to a long price plateau. Then, hopefully, what happens is that during this time, rising incomes and inflation will gradually restore affordability to what it was before the sharp price increase.

This was indeed what happened post-1997 and again in 2010, and perhaps again in 2026/2027, given the smaller quantity of projected BTO projects in those years.

Thus, housing prices don’t drop below a certain point, largely due to HDB’s actions, as a response to the political interest of homeowners.

Conclusion B: Price Decreases are Restricted due to Political Reasons

The Staircase Effect: What Makes It So Dangerous

Conclusion A + B: The combination of occasional price increases caused by unpredictable external market forces, and the fact that price decreases are restricted by constant political forces, leads to a staircase effect where property prices can only go up, even past the point of affordability.

The staircase effect is dangerous, mainly due to two key attributes—the unpredictability of the timing and size of the price spike.

Unpredictable Timing

Should a slowdown in production occur shortly before a crisis like COVID-19, such as the BTO supply tapering from 2017 while Lawrence Wong was the Minister of National Development, the price spike is intensified.

As an open and trade-based economy, it is difficult to completely insulate our system from the shocks of the global crises, which will surely come. Even if good predictions and policies can give us a few months of buffer time, the years of construction required for new HDB flats make the spikes inevitable.

Unpredictable Size

The size of the spikes is also uncontrollable, there is no telling how intense a supply or demand shock will be. It may force the prices up to 1.5x of the preferred affordability rate, or it might force it up to 4x of the rate.

The restriction on price decreases by the HDB, which is welcome otherwise and good in intention, becomes problematic in the face of this. If a market spike catapults us to 4x of the preferred affordability rate, how long will we need to stay there? How much more heavy lifting does income growth need to do in an already pricey labour market to make flats affordable again? And how painful will it be before we get there?

So What Now?

What are we looking to achieve? The most coherent answer would be a gradual increase of HDB prices, in line with income growth, that provides a good retirement for homeowners by allowing them to cash out roughly equal to what they put in (after inflation).

This would be close to the “balance point” that should be struck between homeowners and home buyers.

However, in the presence of this “staircase effect”, how can we achieve it?

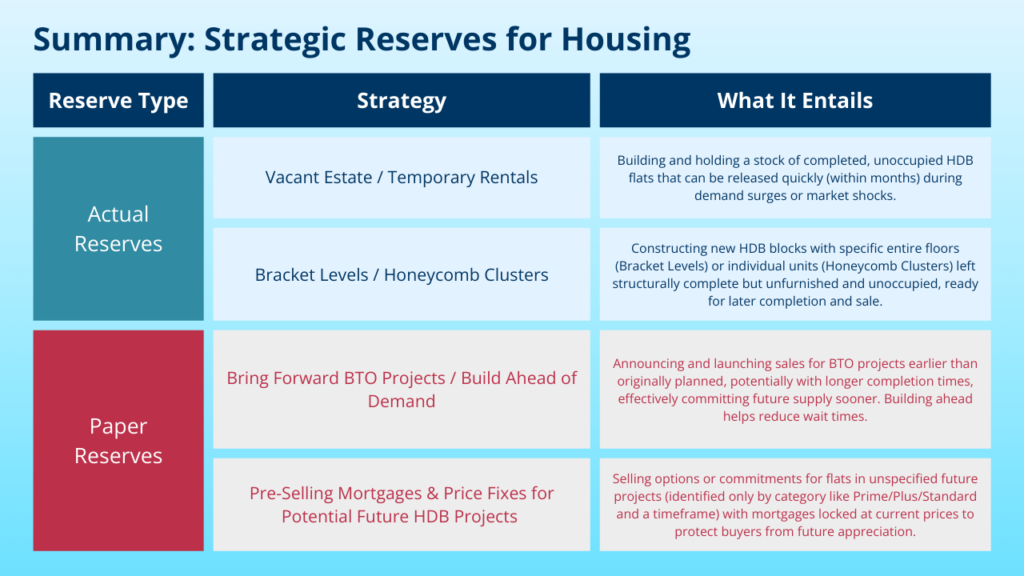

THE SOLUTION: A Case for a Strategic Reserve of Flats

For many other commodities, the only valid way to secure against market-driven shocks in price is a supply reserve. From the granaries of old to the oil futures of today, it is a straightforward way to ensure price stability while the market rides out its sudden fluctuations of supply and demand.

The rainy days of external market forces will surely come, but we don’t know when. The only way we can protect against it is to have reserves set aside when they do. It is very much the philosophy we use for government reserves in other areas, from food to currency.

Requirements of Flat Reserves

There will be costs involved—granaries, after all, must be built from clay and labour. We will investigate those costs together with some possible ways a strategic reserve of housing might be implemented. There are some requirements for such reserves:

List of Requirements

>>> (click each requirement to see more details)

Speed of Release

How quickly the flats are released to the public.Needs to be the same or faster than the speed of the demand increase. A realistic estimate should be around 3 months, but a generous estimate could be 15 months, which is the exclusion period for condominium downgraders.

Amount of Reserves

The number of flats in reserve.Should be sufficiently large. Given that the increase in BTO applications jumped by 37k during COVID-19 and was maintained over 3 years, a reserve size of 40k to 80k in flats would be reasonable.

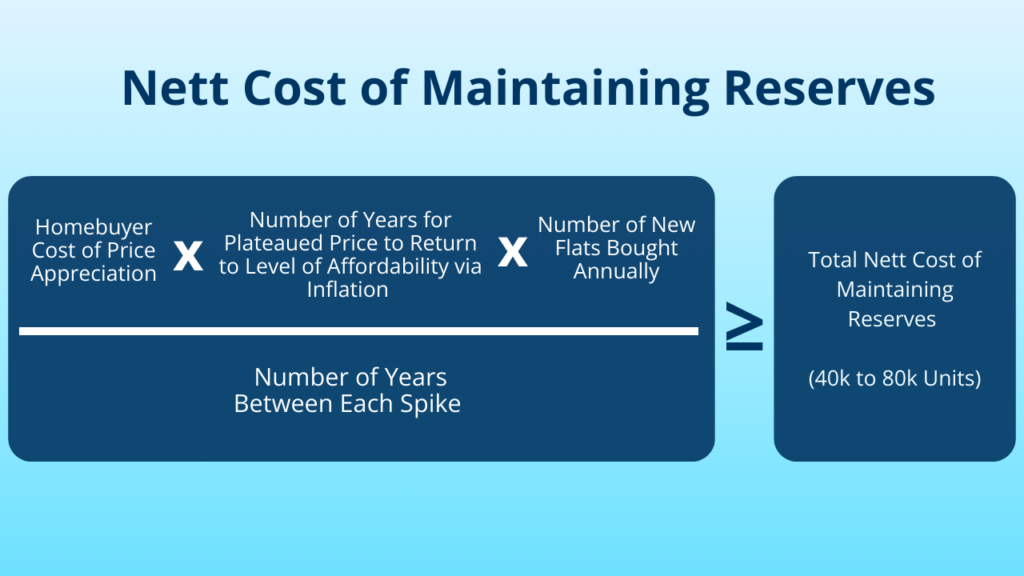

Nett Cost of Maintaining Reserves

How much the government needs to spend to maintain these reserve flats.This cost just needs to be lower than the very high cost borne by home buyers across many years, should there be no reserve to prevent an uncontrolled price spike.

Equation to Calculate Nett Cost

Factors in the Equation

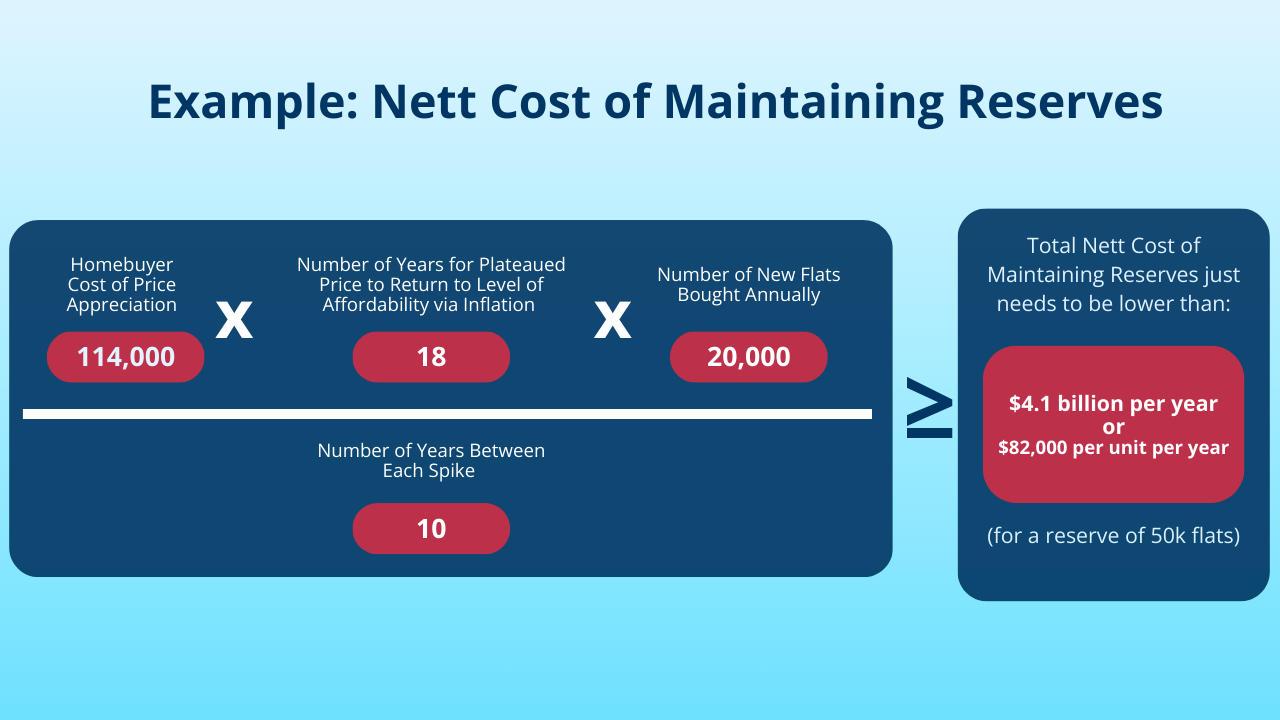

Cost of Uncontrolled Price Appreciation

This is the additional price a home buyer would have to pay for a new flat due to an unexpected price increase.

For example, when a typical resale flats jumped from 464k to 690k (based on similar 4 room flats in Punggol before and after the COVID 19 price spike), there is an additional cost for every homebuyer of 226k. This however will slowly decay with inflation until 690k becomes equally affordable again, working out to an average cost of 114k a year over 18 years.

Number of Years for Plateaued Price to return to level of affordability via inflation

Inflation and income growth are the only ways to increase affordability of flats without reducing price.

We ignore income growth as it may either be natural or arise as a burden on other aspects of the nation. Also as a late stage developed economy, income growth may not even be viable.

So for example at the inflation rate of 2.5% a year, a 690k only will be as affordable as a 464k flat in 18 years.

Number of New Flats Bought Annually

A small reserve has a price control effect over a large market. The lack of reserve means the wider market suffers the costs of the lack of price controls, including every subsequent flat bought.

So for example, if 20k new flats are sold each year, the cost to homebuyers is applied on every one of those flats.

Number of Years Between Each Spike

The reserve must be maintained over the long term, with its cost divided over the average number of years between each price spike.

For example, from the beginning of the last plateau in 2015 to the end of the most recent spike in 2025 there are 10 years.

Based on the above math, we can see there is likely much room to work with for the nett cost of maintenance, to the tune of $82,000 per unit per year.

The Capital Cost of Building Reserves

How much the government needs to spend to build these reserve flats.This should be feasible and not unrealistic. Even if they are higher, as long as the interest cost of the capital does not raise the nett cost of maintenance above the threshold, it is not unfeasible.

Retention of Value

Value of the reserve flats over time.Ideally, the reserves should not expire, or if they do, have a significantly large recoverable cost.

Potential Generation of Income

Opportunities for the government to generate income from the reserve flats.If possible, the reserve units should also be able to generate income while in reserve, ideally without degrading their value whilst offsetting and lowering the nett cost of maintenance.

Administered by HDB

Reserve flats are supplied and controlled by the government.Finally, it must be administered by HDB. In a fully free market, a reserve may eventually be built by private individuals, who buy in low slumps and store to sell in high peaks—thereby moderating the price spikes with their private reserves. However, with a downward restriction on prices, there is no slump to buy low. Therefore, holding one’s assets indefinitely rather than selling at peaks is the most profitable way to treat one’s assets. On a more practical note, to prevent entrenched landlordism, ownership laws generally forbid any private entity from holding massive reserves of HDB flats. Thus, only HDB (or by extension, the government) can be responsible for this.

With these requirements in mind, we go into some possible ways to build a strategic reserve—some of which have already been partially practised with some positive effect, but do not go far enough because they lack the scale or speed necessary to respond to the extent of the market shock.

Vacant Estates

This is the most obvious way to go about building a reserve, and unwittingly occurred for a short period after 1997. About 31,000 flats ended up unexpectedly in reserve, and sources differ on how long it took to clear the stock (ranging from 1 year to 5 years).

Imagine if that reserve was not cleared and had coincided with the next spike event (e.g. COVID-19). The 31,000 flats would have cleverly played off most of the 37,000 spike in BTO applications and cooled the market significantly.

The main issue with this strategy, according to the CNA documentary, is the Service and Conservancy Charge levied on these flats that the HDB had to pay. Even if we take the highest end of the $100 monthly charge, it is $1,200 per unit annually, or $37.2 million across all the units per year.

Framed as a cost of a planning hiccup by the government, it is no small sum. However, if considered as a strategic reserve that protects the entire nation’s flat prices against market spikes, it’s not very expensive. To compare, we have toilet grants of 10 million.

Let us see how it fares in the other areas:

Speed of Release

- Either immediately or within 3 to 6 months of renovation.

- Fast enough to absorb demand shocks that create immediate actual housing needs.

Amount of Reserves

- Building a reserve stock of 40 to 80k would be possible, but it will require the appetite and political will of the government to do so.

- By keeping our BTO production speed at 20k and setting aside a quarter of it, a sufficient reserve could be built up in 8 years, which would be about time for the next crisis.

Nett Cost of Maintenance

- $1,200 per unit per year, not including lease decay.

- The lease decay is negligible if flats are sold on immediate release, as the amount buyers are willing to pay for immediate access would be more than the loss of value via lease decay.

- The government can opt to extend the lease if necessary.

Capital Cost of Building

- Large but not unfeasible. At a development cost of roughly 395k per unit, this would put the capital cost of a 40k reserve at $15.8 billion.

- At a 2.7% interest rate, this would be $426 million annually for the entire reserve or 10.6k per unit per year. To put this into perspective, 2025’s expenditure on CDC vouchers is $780 million.

- While high, this cost is as the price stability benefits on the rest of the market are much higher.

- If you waive the land cost and/or the interest on the land cost, the interest rate would be even lower.

Retention of Value

- Any cost of lease decay experienced by the flat is likely compensated for by charging more for the right of immediate access.

Potential Generation of Income

- If flats are first rented out to young couples, singles, and/or foreign labour on annual leases at a much lower than market rate ($1000 to $1500 a month), it would actually be more than the cost of maintenance and the interest charge on the capital combined.

- Tenant management, rent, and making sure tenants obey the leases and move out when vacancies are sold may be tricky, but not impossible to overcome.

The release of these flats would be on a first-in, first-out basis, with units leaving the reserves regularly and new projects entering the reserve regularly.

The increased speed of getting keys versus waiting for BTOs can also justify charging a price closer to the ideal resale price (instead of a discounted BTO price), with this money helping to offset the nett cost of maintenance.

As the reserve builds up over years of low demand to the upper limit, then production can slow down. Due to the reserve’s protection this slowdown can occur without the fear of a sudden market shock. During market shocks, the reserve will deplete as our first line of defence, and production will be given more time to ramp up and refill the reserve.

Bracket Levels / Honeycomb Clusters

There is, however, some concern about the bad image, squatter risks, and maintenance fees for full vacant estates. Here is an alternative that provides a similar function, but is an improvement over vacant estates in these areas.

The inspiration is based on Chua Beng Huat’s illustration of kampung houses as well as the Vietnamese “tube houses”, where as residential pressures intensify, expansions are added to existing buildings via horizontal attachments or vertical new floors. To adapt existing buildings to fit more families as the population grows seems to be the natural tendency of human beings. More perversely, the segmentation of condominiums into small sub-units to fit more families in Hong Kong (and some units in Singapore) is an attempt to do the same within the constraints of modern concrete apartments.

Bracket Levels refer to a standard HDB flat plan, however, with one in every 2 or 3 levels left vacant. The structural walls of the units on the vacant flat will be built up but with no degradable furnishings—the idea being to allow the flat to be held for up to 5 years without degradation, and if needed, sold immediately and renovated into a livable condition within 3 to 6 months. The floor and lift access to these levels will be locked and only accessible to maintenance staff to prevent squatting.

If there is a special need to monetise the reserves which the usual HDB buyer market cannot absorb, some of these units can be sold to the households directly above or below them to expand into 2-storey units. The absence of such HDB units elsewhere would make this quite attractive and represents a way for HDB to further secure the value of their reserves.

Using bracket levels for reserves also allows HDB to build higher-density projects in non-mature estates without being limited by expected short-term demand. The current low number of floors in some non-mature estates is regrettable, given that the technology to build higher floors has been with us for some time. With bracket levels, the HDB can build higher and simply let the demand roll in over time.

Honeycomb Clusters refer to a standard HDB flat plan, however, with 1 in every 2 or 3 units left vacant, such that every vacant unit will neighbour an occupied unit. The structural build-up and furnishing requirements are similar to those of bracket levels, but with the individual units locked rather than an entire floor.

The special monetisable action of these reserve units would be the purchase of the adjacent flat by the occupying neighbour, who would then knock down a wall to join the floor plans of the two units. This would be more reasonable, as it is an existing practice for some families living adjacent to each other.

The incorporation of vacant reserves together with occupied flats also allows for the same higher density build-up mentioned earlier.

The key advantage this has over the Vacant Estates model is that the estates are still occupied, and the conservancy charge of maintaining the estates themselves is borne by the existing occupiers. The marginal added costs of maintaining the reserve units may still be there, but are likely much lower and can be more easily covered out of HDB’s budget.

As an alternative to vacant estates, these units would have similar reserve release policies as vacant estates—being cycled out within 5 years on a first-in, first-out basis.

Speed of Release

- Either immediately or within 3 to 6 months of renovation.

- Fast enough to absorb demand shocks that create immediate actual housing needs.

Amount of Reserves

- Building up the reserve stock this way might cause BTO projects to take longer to finish, as additional levels need to be added.

- However, the average waiting time is then decreased as new buyers can opt for either BTOs or buying from reserves as their first home purchase.

- The ability to build higher-density projects is also good for long-term planning, as it prevents the nasty issue of potentially demolishing and rebuilding shorter HDB flats as the estates mature.

- Regardless, if we keep up our current building speed and have 1 in every 3 levels/units of current HDB projects set aside as strategic reserves, we would build up a 40k reserve in 6 years.

Nett Cost of Maintenance

- Lower than the Vacant Estates model, as estate-level services are still paid for by the occupied households.

- Some fees may be necessary to ensure the cleanliness and safety of the vacant units/levels, but they should be substantially lower than $1200 per unit per annum.

Capital Cost of Building

- It would be similar to the Vacant Estates, but significantly lower due to the land cost being divided by a larger number of units via this reserve policy, allowing for higher-density projects.

Retention of Value

- Similar to the Vacant Estates model, but additionally secure.

- In the unlikely event that poor planning leads to an overbuild up of reserves and results in some strain with the capital interest cost, some vacancies can be offered for sale to adjacent occupied units, who have the unique opportunity to expand their family home.

- Given the significant popularity of “jumbo” flats on the resale market, this would be a good deal for both the buyers (who have a non-condo upgrade path) and the government (who can tap into the buyers’ upgrading budget for capital).

Potential Generation of Income

- Same as vacant estates, the government can consider renting out the vacant reserves, but only if there is the administrative will to handle the logistics of it.

Land Reserves

To be complete, we must consider that the land reserves themselves are also a reserve. They fail, however, in the timing of release—though there are ways to improve this, which we see in the next sections.

Speed of Release

- Too slow, and land reserves by itself is not a valid purchasable product for home buyers.

Amount of Reserves

- Plentiful. Singapore is not as land-scarce as imagined.

- Undeveloped land reserves are still plentiful, and many low-density private housing estates are still valid for redevelopment if there is political will for it.

Nett Cost of Maintenance

- None.

Capital Cost of Building

- None.

Retention of Value

- No loss.

Potential Generation of Income

- Not needed.

Bring Forward BTO Projects / Build Ahead of Demand

(e.g. Ulu Pandan Glades)

To give the government credit where they deserve it, in the middle of the pandemic, where no supply could be found, they still managed to squeeze blood from a stone and offer some supply relief to the BTO market.

The way they did so is to bring forward BTO projects with longer wait times (5.6 years on Ulu Pandan Glades) which otherwise would not have been announced so soon, essentially transforming land reserves into purchasable objects which Singaporean buyers could put their money into—securing a price before the market inflates further and a peace of mind that one will have place to stay in the future.

The ideal group of purchasers this would satisfy would be the families who brought forward their purchase due to the rapid price appreciation, as the longer wait time would fit into their original life plans.

The problem, however, is that given the immense fear of wiping out savings, normal buyers might also ballot into these projects. The long wait time then delays marriage and childbearing for them, which might be uncomfortable.

In theory, this is not a bad idea—there are three main issues: (1) the long wait time, (2) it was not done to a great enough extent to cool the overall market, and more importantly, (3) it does not resolve the immediate price pressures borne on the resale market directly by condominium downgraders and others in need of actual housing.

The wait time and the extent issue could be resolved by building ahead of demand, allowing the timeline extensions from a 1-year to 3-year wait for a moderate number of supply release, or to go from a 1-year to 5-year wait for a large amount of supply release, giving the government a bigger toolbox to tackle potentially large market shocks.

The fear of building ahead of demand is, of course, vacant units, which is a smaller concern if the Bring Forward reserve policy is adopted in conjunction with the Vacant Estates Policy or Bracket Levels/Honeycomb Clusters Policy, as vacant units simply go into the strategic reserve instead of being seen as a waste.

The inability to provide actual housing, however, is still a core limiter of this policy—it may resolve panicked demand, but sometimes actual demand may be the driving force, which calls for a combination of this with a hold of a reserve of actual vacant housing units.

Speed of Release

- Fast enough for panicked buyers, and immediately if properly prepared. The HDB can simply announce the bring forward of projects at will and is limited only by the administrative preparation needed to do so. If they have the staff earmark some later projects specifically to bring forward for supply reserve purposes, they can theoretically do this action fast enough to satisfy a sudden surge in demand.

- Too slow for actual housing needs, which will still put pressure on the resale market. We saw some of this in the increased need for actual housing by Singaporeans that needed to work from home, or from PRs who could not transit from Malaysia. It is conceivable that a future event (e.g. the mass repatriation of overseas Singaporeans) could be a possible demand shock based on actual housing demand, where this “paper solution” will have no effect.

Amount of Reserves

- Assuming a build speed of 20k flats per year, for each year of projects brought forward, the HDB can add another 20k.

- By extending the build times by 2 years, a 40k reserve can theoretically be realised.

- However, elongated build times will put a strain on buyers eventually. Building ahead of demand would in turn reduce this strain.

Nett Cost of Maintenance

- None, as this is a “paper reserve”.

- The burden of the reserve is shifted from the government to the buyers, who must endure a longer wait time.

Capital Cost of Building

- None, as this is a “paper reserve”.

Retention of Value

- Not necessary.

Potential Generation of Income

- None, as this is a “paper reserve”.

Pre-Selling Mortgages & Price Fixes for Potential Future HDB Projects

This would be a step further on the strategy of pre-selling brought forward BTO projects, where HDB sells projects which have not even been conceived.

Under this strategy, HDB would sell upcoming projects classified as “prime”, “plus”, or “standard”, and provide a range of completion years. Importantly, mortgages would be locked in at current prices to protect buyers from rapid price appreciation in the future. The buyer pays to HDB a deposit at this current price, and thus gets the option to buy into these future projects at such the current day’s property price.

While extreme, this model offers two potential benefits: Firstly, it could help manage housing supply constraints during major crises (like COVID-19). Secondly, it has a unique appeal to singles by enabling them to buy before age 35, alleviating their major unhappiness at not being able to lock in a favourable property price earlier in life.

Speed of Release

- Same as brought forward projects, technically instant if there is sufficient administrative preparation beforehand.

Amount of Reserves

- Technically infinite.

Nett Cost of Maintenance

- None, as this is a “paper reserve”.

- One possible issue for HDB is inflation—the risk of future development costs exceeding the revenue collected at earlier prices.

- To address this, HDB could add an “appreciation charge” later, calculated in a way that is fair to HDB, homeowner, and home buyer.

Capital Cost of Building

- None, as this is a “paper reserve”.

Retention of Value

- Not necessary.

Potential Generation of Income

- None, as this is a “paper reserve”.

Intended Performance

A practical strategic reserve strategy will likely be a mix of the above policies (and possibly many others to consider), but must always include actual housing reserves in addition to “paper reserves”.

With a strategic reserve in place, when the next wave of market shocks come (and they surely will), there is resiliency in the system, and HDB will have answers to both increases and decreases in price.

During the demand spike or supply slow down, vacancies from the reserves can be released into the market at the current resale price to to soak up the unfulfilled demand and maintain price stability. For reserve sales that include actual housing units, the “profit” from forgoing the BTO discount would also work nicely to cover any accumulated reserve maintenance costs.

Where the solution is BTO-based, the total amount of unbuilt flats to be bidded on can be expanded by drawing from both actual and “paper” reserves, soaking up urgent bidders who would otherwise pump up the demand in the resale market.

As the housing price maintains its stability, prospective buyers can trust that there will be no rapid appreciation in prices that would wipe out their savings, and feel safer to put off their purchase to a later stage of life. Thus, preventing the mass “bring forward of purchase” effect that further inflames the market.

Therefore, a sufficient lever of control is achieved for both upwards and downwards price changes. HDB thus makes use of its status as both the monopoly supplier (who can reduce supply at will) and the reserve holder (who can increase supply at will) to maintain the price at the ideal balance between affordability and appreciation—balancing the needs of home buyers and homeowners whilst giving confidence to the whole system.

This could be the “magic wand” Lawrence Wong desperately needs.

Final Thoughts

I write this with some hope that it will be discussed over the General Election Period. I hope it will be!

Singapore as a nation with no hinterland has economic relevancy as its central concern, and for this relevancy, it has human capital as its major resource. That human capital is getting quite expensive nowadays—businesses are feeling the pressure, and employees are having a tougher time finding jobs that “pay enough”.

It may be argued that from cars to premium education to annual holidays, much of what makes Singaporeans expensive might be considered non-essential, and when push comes to shove we might be able to work with less.

However, in one critical way it is not, and that is the price of the HDB.

Affordable HDB should be a driver of economic relevance, instead of being a cost/burden that necessitates continuous income growth.

This is why, save the presence of an alternative solution, I feel quite strongly that the building of a strategic reserve of HDB flats must be considered.

Main Resources:

- Public Subsidy Private Accumulation (B.H. Chua, 2024).

- CNA Documentaries: Has Housing Become Unaffordable & When Will I Get My Home?.

- A lived experience of buying a flat in the middle of the rapid post-COVID resale price inflation.

- Peer experiences of long BTO build times and expensive BTO prices.

Secondary Resources:

- HDB’s 2023/4 annual report.

- The 6th Feb 2023 parliamentary debate on HDB.

- Mainstream journalism’s reports on HDB issues since COVID-19.